Andrei Tarkovsky's 'Stalker': An Exploration into the Abyss

Tarkovsky uses the frame of science fiction to explore the human psyche and its punishing search for meaning and happiness

It has taken me too long to finish this essay. I liked the movie ‘Stalker’ and I felt the need to write about it. There was something about the characters, the plot, the visuals, and the music which drew me in. And I wanted to think about this great film and understand it better. I was fascinated by the philosophical underpinnings of the characters and how profoundly these manifest in their words and actions, in their ideas about meaning and purpose. On the surface of it this film is about human longing — the expedition of three men into a mysterious Zone to get what they want. But at its heart, this film is about torment and misery. Every major character in this films is cracking under the weight of existence; see it in their sunken eyes and wizened faces, hear it in their plaintive voices. And the film wears its heart on its sleave. Sample this conversation:

Writer: “All my life I have never seen a single happy person.”

Stalker: “Neither have I.”

And this bleakness is pervasive. A film about longing has to also be a film about torment. What else can it be? Those are the two sides of the same coin, to use that threadbare expression.

So what is this movie trying to say? What is the takeaway here? Why do I find it so fascinating?

It is difficult to pin down what this film is really trying to say which also makes it so fascinating to watch. But let’s give it a try.

A mysterious Zone, formed due to a meteorite impact or an alien visitation (perhaps), is claimed to have a room which can grant the innermost desire. The Zone, now an uninhabited area governed by a strange force, has been cordoned off completely by the government. But there are men, known as Stalkers, who can guide the inquisitive cross into the Zone for a consideration. One such Stalker is ready to go on his mission to the Zone with a writer (known in the movie simply as ‘Writer’) and a professor (known as ‘Professor’). All three men have their own purpose pushing them into the Zone.

This is the synopsis of the film.

Wikipedia entry about the movie says that Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1979 science fiction philosophical film Stalker is based on the novel Roadside Picnic by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky. A number of science fiction films have used some variation of ‘hapless explorers walk into a mysterious place only to find demons / monsters, either manifested in reality, or in their own psyche’. TV shows (like Lost) and films (the Alien franchise, Annihilation and many others) have done that. Stalker would scarcely appear to be a conventional science fiction film to modern viewers: there are no special effects (except one epilogue like scene at the very end), no high end weapons, no hideous monsters, no extraordinary powers, or mysterious shiny stuff. Even the room granting wishes, which is at the core of the whole conceit, is not shown (we go as far as its threshold, don’t even get a peak); its mechanics remains shrouded, and its powers are only spoken of but not demonstrated. What Stalker really is is a great philosophical drama which uses science fiction as a scaffolding to build a story with some of the best character revelation and rich dialogue that I have found in a film. Within its sepia monochrome frames it captures the individual anguish of its protagonists.

The films opens with a scene of Stalker at his house (Alexander Kaidanovsky playing Stalker) with his wife and daughter. He is getting ready for his mission into the Zone. His wife pleads him not to go. She believes he would be captured and imprisoned, again — this time for ten years. But physical captivity is not the only kind of captivity.

"Prison"? I'm imprisoned everywhere.

The films then introduces us to the Writer (the brilliant Anatoly Solonitsyn) who seems jaded and caustic. He finds the world unbearably boring, bound by rules of Physics and Mathematics; too predictable, as is his writing. Exhausted and at the end of his talents, he finds writing pointless. There is no sense in writing about anything. There never was, perhaps. Part intrigued and part skeptical, he goes looking into the Zone.

I have lost my inspiration. I am going to beg for some.

This trio is completed by the Professor (Nikolai Grinko) who is also going for scientific exploration.

As the story unfolds, these outward purposes will turn out to be mere covers for deeper wounds and darker agonies. We seldom tell others what we want. We don’t necessarily know ourselves what we truly want. Is it possible to know? Can we really choose what we want? We are all wanting machines, forever wanting, to quote Charlie Kaufmann. What we want keeps changing constantly.

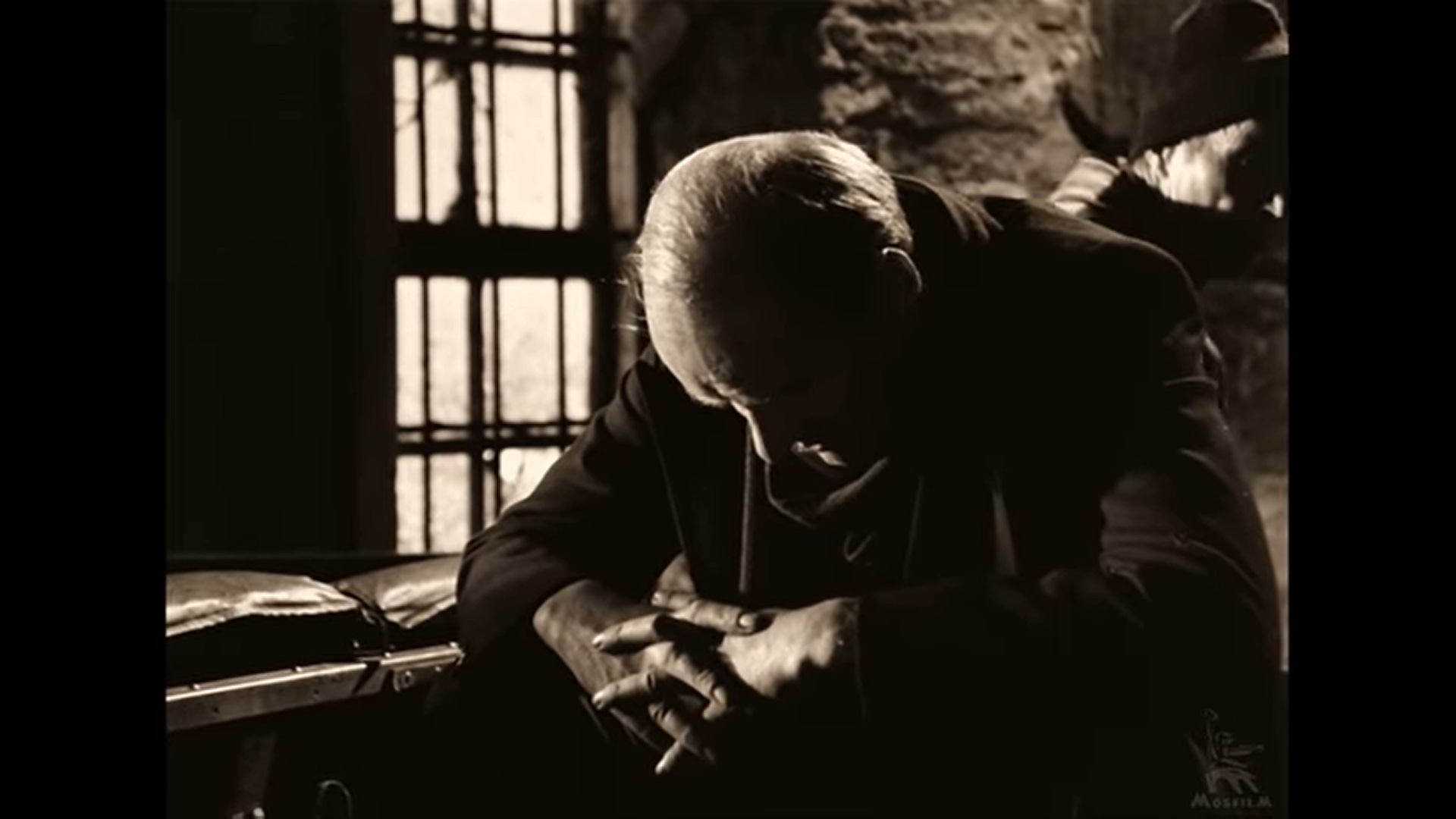

The film shows the three men hiding in wait in one of the shabby warehouses near the railway tracks, attempting to evade the security and cross over into the Zone. The Writer is sitting, his head bowed and his fingers entwined. He lifts his head slightly and speaks apropos of nothing to no one in particular:

What I said about going there.. it’s all lies. I don’t give a damn for inspiration.. and then how can I give a name to what it is that I want? ..

My consciousness wants triumph of vegetarianism. My subconscious longs for a juicy steak. So what do I want?

It is important to locate the center of our being even if it seems an impossible thing to do. The Writer is beginning to unravel at the edge of the Zone. He is miserable. He finds his writing meaningless and worthless. He came thinking that if he got what he wanted — perhaps write a novel which would be read by people for hundreds of years — he would be redeemed, his suffering would be lifted. And now he is not even sure about that. He is also skeptical of any otherworldly power which can soothe his pain and lift his torment. The real exploration into the Zone and the metaphysical exploration into the question ‘what do I want?’ walk hand in hand.

The three hop onto a railcar and scenery changes from industrial design of railroads and warehouses to lush green wilderness with waterfalls indicating they are getting closer to their destination. It is a strange juxtaposition of images. Once they reach, the Stalker is ecstatic, finally being somewhere he belongs, where he finds meaning. He is at the altar of his church. He was in jail for five years for stalking. This is his first mission since his release. This feels to him like catharsis. He drifts away from the group and kneels and then prostrates on the ground as though in prayer. Anywhere else in the world he might be a nobody, but here in the Zone he is a navigator, a guide to the forlorn, a facilitator of desires. He is in the warm embrace of the Zone.

They proceed and they are soon in close proximity of the place they have come looking for. The Writer is reckless and edgy. He disregards the advice of the Stalker and follows the path leading straight to the complex only to turn back as he hears a voice telling him to stop. The Stalker warns the others about the dangers lurking in the Zone.

The Zone is a very complex maze of traps.. Former traps disappear, new ones appear. Safe ways become impassable and the path becomes first easy, then incredibly confused. This is the Zone. It might seem capricious but at each moment, it’s just as we have made it, we and our state of mind.

.. everything that happens here, depends on us, not on the Zone.

This is where the story refracts into multiple possible interpretations: as a work of science fiction about exploration of a mysterious Zone and as an allegory of human being’s exploration of life (Note: Many have explored religious, environmental, and political interpretations of the film too). It’s just as we have made it, we and our state of mind — an echo from the Buddhist philosophy — how we choose to see the world determines the nature of our experience; we are the masters of our experience, not the circumstances.

The film’s second part begins. Stalker is gazing into a well. A circle of water swaying and roiling surrounded by walls of darkness. It is the power of this film that disturbance on the surface of water and light reflected from it becomes one of the most captivating scenes on screen. We hear the Stalker’s monologue in the form of a prayer:

May everything come true. May they believe. And may they laugh at their own passions; for what they call passion is not really the energy of the soul, but merely friction between the soul and the outside world. But, above all, may they believe in themselves and become as helpless as children, for softness is great and strength is worthless.

A prayer indeed. Next to a ‘wishing well’, too. The above quote is a paraphrase from Tao Te Ching, a reflection of the Lao Tse’s philosophy of Taoism. Taoism teaches that our passions and desires are our rebellion against the flow of existence. We are not satisfied with being in harmony with the universe. It is not enough for our ego (Note: A wonderful poem on this theme appears later in the film). We want to win; we want to bend the world to our will. And since it is impossible — a part can never win against the whole — this friction breaks our spirit and causes unbearable torment. Therefore Taoism teaches us to be nimble and soft and light in our existence, allowing the ego to sublimate, and embracing the flow of universe and not fighting it.

I can also think of Tarkovsky giving a nod (or a wink) to the famous quotation by the existentialist philosopher Nietzsche with the imagery of the Stalker staring down the abyss.

Beware that, when fighting monsters, you yourself do not become a monster... for when you gaze long into the abyss. The abyss gazes also into you.

— Nietzsche

The group pauses near a water stream and rests on the wet mud. The old question of why they have come into the Zone resurfaces. The Writer and the Professor engage in mutual back and forth, and scoff at one another’s motivations for coming into the Zone. Nobel Prizes are talked of. It is quite entertaining. But here is one of the more illuminating exchanges:

Professor: Want to bestow on mankind the pearls of your bought inspiration?

Writer: I spit on mankind. Only one man interests me, namely me, myself.

The sheer blunt force of this statement gave me a pause. In our civilized society in which perforce some degree of dissimulation of caring for others is warranted for the social theater to go on in perpetuity, even when we have mastered the dissimulation, it can be surprisingly hard hitting to come across something like this — even in a film — which we stealthily yet inescapably know to be true already.

I think of a memorable quote from David Foster Wallace:

Everything in my own immediate experience supports my deep belief that I am the absolute center of the universe, the realest, most vivid and important person in existence. We rarely talk about this sort of natural, basic self-centeredness, because it's so socially repulsive, but it's pretty much the same for all of us deep down. It's our default setting, hard-wired into our boards at birth. Think about it: There is no experience you've had that you were not at the absolute center of.

‘I’ sits at the center of all conscious experience. The Writer, having jettisoned all the facades in the Zone, has nothing but seething contempt for humanity. He is not trying to convince or win over anybody. Somebody criticizes him, somebody praises him. He has played that game. He doesn’t care. He is here to redeem himself. But, can he?

The Writer and the Professor then turn to the Stalker. This man has brought scores of people to the Zone. Why did all of them come here? The Stalker answers that he doesn’t know because ‘people don’t speak about their innermost thoughts’. The conversation turns to music, art, self expression, science, and ultimately meaning of it all.

For everything in the long run has meaning. A meaning and a reason.

They walk through a tunnel and ultimately reach the threshold of the room. The Stalker recites a poem which I liked very much (this is the poem I have referred to above). I believe it is written by Andrei’s father:

Now the summer is passed,

it might never have been;

It is warm in the sun,

but it isn't enough;

All that I could attain,

like a five-fingered leaf,

fell straight into my hand,

but it isn't enough;

Neither evil nor good

has yet vanished in vain;

It all burned and was light,

but it isn't enough;

Life has been like a shield

and has offered protection;

I have been very lucky,

but it isn't enough;

The leaves were not burned,

the boughs were not broken;

The day shines like glass,

but it isn't enough.

It isn’t enough. If there is a central theme in this film it is this: it isn’t enough and we struggle with it. It isn’t enough because it can never be. It is our curse.

Stalker is happy that he has finally brought his entourage safe to the Room. For the first time, we spot a momentary glimmer of something akin to contentment on his face. He is the priest of this church and and he has brought the believers safely to their deliverance. But this is not a movie about deliverance. They stand before the threshold to the room. This is the moment of reckoning. The seekers should be excited. Their deepest desires are about to come true. They have to just extend their hands and take it. But they have never appeared more tormented, more tired.

The Stalker asks the Writer to go in. But The Writer doesn’t think the Room grants what one wants. The Room grants one what is the essence of oneself — one’s truest desires. And no one is able to know what their innermost desires are.

What comes true here is that which reflects your true nature. The most secret desire. It is within you. It governs you. Yet you are ignorant of it.

He refuses.

The enigmatic Professor ultimately reveals his true motivation. He has brought a bomb to blow up the whole place. He is here to save humanity from its worst impulses.

Imagine what will happen when everyone believes in this Room and when they all come hurrying here. It's only a question of time. Not today, but tomorrow. And in the thousands. All these would-be emperors, grand inquisitors, fuhrers of all shades. The so-called saviors of mankind! And not for money or inspiration, but to remake the world.

The Stalker attempts to snatch the bomb away, but is overpowered by the Writer. The Stalker wails that this is the only place for him in the world. He pleads the Professor to not destroy it.

There is nothing else left to people on Earth. This is the only place to come to when all hope is gone. You did come here? Then why destroy faith?

..

Everything I have is here. Here, in the Zone. My happiness, my freedom, dignity, everything is here.

Eventually, the Professor drops his plans to destroy the room, disassembles the bomb and throws away the pieces into the water pooled around. No one even sets foot into the room. The writer almost falls into the Room, but the Stalker grabs his jacket and pulls him back.

The Writer and the Professor both do not take the decisive step. One doesn’t go in to take advantage of the Room; the other does not destroy it though he believed it to be a threat to human civilization. How feeble beliefs are; even the ones held so strongly crumble under the weight of the moment.

The three, more hopeless and dejected than ever huddle together in the morass of the Zone. I have never felt more depressed for characters in a movie.

If this sequence of events is frustrating or perplexing to the viewers, it is deliberate on part of Tarkovsky. Stalker says:

I don’t understand anything at all. What is the sense in coming here?

What is the sense in coming here? What is the point of reaching all the way to the wellspring and then not drink?

I don’t know. This is not a film which ties up everything neatly because life doesn’t tie up everything neatly. Nothing is ever resolved. There is no fulfillment. There is never any clarity. The film has been building up to something precisely like this. It was not going to solve anything for its heroes, or its audience.

In the next scene, the three are back at the rundown bar where they met initially. At home, we find the Stalker distraught to the point of sickness. If the people he brings there will not even use the Room due to vanity or doubt, what is his purpose now?

They call themselves intellectuals. Writers. Scientists. They don’t believe in anything. Their capacity for faith has atrophied.

..

They are thinking how not to sell themselves cheap, how to earn more, how to get paid for every breath they take. They know they were born to be someone, to be special. How can such people believe in anything at all?

And finally the film shows the Stalker’s wife (Alisa Freindlich) speaking directly into the camera. She speaks about her life with the Stalker, how she decided to marry him despite her mother advising against it.

I knew there would be a lot of sorrow. But I’d rather know bitter sweet happiness than a grey, uneventful life.

And if there were no sorrow in our lives, it wouldn’t be better, it would be worse. Because then there would be no happiness either. And there would be no hope.

If there were no sorrow in our lives, it wouldn’t be better, it would be worse. May be it will be the ruin of man to see the fruition of his most cherished desires. Who is to say?

Stalker is a film which leaves you with a great many ideas. It has such hypnotic visuals that every frame can be a beautiful wallpaper. The background score is a masterpiece composed by Eduard Artemyev. It is an allegory, a commentary on human nature, a religious tale and a political critique and so much more. I loved this film and it has taken many more hours to write this thinkpiece (such a phony word!) than it took me to watch the film. But it is a pleasure to think about these things. They don’t make movies like this anymore. It is available on YouTube and can be watched using the link below. Enjoy!